A couple of months ago (really, a long, long time ago) I found an interesting question on Mathematics Stack Exchange (another site to effectively waste away hours of your life). It reminded me of my Bachelor’s thesis (which I wrote a really, really long time ago) about the sequence

\[ g_n=\mathrm{gcd}(n,a_{n-1})=(n,a_{n-1}) \quad\text{for}\quad n>1, \]

where \(a_1=7\) and

\[ a_n=a_{n-1}+g_n. \]

Here, \(\mathrm{gcd}(a,b)=(a,b)\) stands for the greatest common divisor,1 i.e., the largest integer \(d\) that divides both \(a\) and \(b\). This may not seem terribly interesting at first sight, but if you look at the first few values for \(g_n\) you’ll notice something curious:

1, 1, 1, 5, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 11, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 23, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 47, 3, 1, 5, 3, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 1, 101…

There are for sure a lot of ones in there, but other than that, all the numbers are primes. This is not a bias in the first few example – Eric Rowland proved that all values of \(g_n\) are either \(1\) or a prime in a beautiful little paper back in 2008.

I can’t help but getting a little sentimental here – this was the paper my supervisor assigned to me for my undergrad thesis, and the first research paper I really got my teeth into. The beginning of a wonderful journey!

The proof is far from difficult and a good overview of follow-up articles is given on bit-player.org. But it wasn’t Rowland’s sequence the question on MSE was about, but instead a similar one that uses the lowest common multiple (\(\mathrm{lcm}(a,b)=[a,b]\)) instead of the gcd:

\[ q_n=\frac{[n,b_{n-1}]}{b_{n-1}} \quad\text{for}\quad n>1, \]

where \(b_1=1\) and

\[ b_n=(q_n+1)b_{n-1}. \]

When we look at the values of this sequence, you’ll spot a similar pattern to the one above:

2, 1, 2, 5, 1, 7, 1, 1, 5, 11, 1, 13, 1, 5, 1, 17, 1, 19, 1, 1, 11, 23, 1, 5, 13, 1, 1, 29, 1, 31, 1, 11, 17, 1, 1, 37, 1, 13, 1, 41, 1, 43, 1, 1, 23, 47, 1, 1, 1, 17, 13, 53, 1, 1, 1, 1, 29, 59, 1, 61, 1, 1, 1, 13, 1, 67, 1, 23, 1, 71, 1, 73, 1, 1, 1, 1, 13, 79, 1, 1, 41, 83, 1, 1, 43, 29, 1, 89, 1, 13, 23, 1, 47, 1, 1, 97, 1, 1, 1, 101…

The sequence seems to be much richer in non-one values, but this comes at a price: We don’t know if there are any composite values in the sequence! Benoit Cloitre announced a proof in Rowland’s original paper, but hasn’t delivered on his promise as of 2015. One thing that is very easy to prove is that every prime (except for \(3\)) is a member of the sequence – a nice fact, given that we have very little knowledge of the values that appear in Rowland’s sequence.2

My answer to the MSE question made me think about the problem again, and instead of the pages of awkward arguments it took me in my thesis I came up with a very simple and short proof. However, the question is about a slightly different sequence, and I wasn’t able to use the same short cut to the definition above. Please do let me know if you find a shorter argument!

First, we need the trivial connection between gcd and lcm:

\[ (a,b)\cdot[a,b]=a\cdot b. \]

This is best understood if you compare the prime factorisation on the left and the right hand side: For every prime \(p\), we have the highest power \(p^k\) that divides \(a\) and \(p^l\) that divides \(b\). The smaller of the two will be part of the gcd, the larger part of the lcm. United in products, both sides will yields the same result.

If we apply this formula to \(q_n\), we obtain

\[ q_n=\frac{n}{(n,b_{n-1})}. \]

Equipped with this, it’s now easy to conclude that we must have either \(q_p=1\) or \(q_p=p\) for every prime \(p\) since the gcd in the denominator can only be \(1\) or \(p\) itself. In order to prove \(q_p=p\) (for primes bigger than \(3\)) we need to prove that \((p,b_{p-1})=1\). For this we need to show that \(b_n\) only has “small” prime factors, and in particular that the largest prime factor of \(b_{p-1}\) is strictly less than \(p\). Once we got this fact, we immediately see that \(q_p=p\) for all primes \(p>3\), and so all primes other than \(3\) are included in the sequence \(q_n\). Since we further have \(q_n\le n\), this also implies that every prime can appear earliest at position \(p\), and hence when we regard only increasing primes in the sequence we will end up with a full list of primes (except for \(3\)).

So, it remains to prove that \(b_n\) has only small prime factors. This in turn follows from the fact that \(q_n\) is odd for all \(n>3\). If this is true, then we can write

\[ b_n=(q_n+1)b_{n-1}=2mb_{n-1} \]

for some integer \(m\le n/2\), and we can argue inductively that all factors in \(b_{n-1}\) must be small (i.e., less than \(n\)), as well as \(m\) and \(2\), so no prime factor in \(b_n\) can exceed \(n\).

Now, for odd \(n\) it is obvious that \(q_n=n/(n,b_{n-1})\) is odd too. So let \(n\) be even. Then we can write \(n=2^kr\), where \(r\) is odd and \(k\) must be less than \(\log_2n\). On the other hand, we can argue again inductively that \(b_{n-1}\) must have at least \(n-3\) factors \(2\) – at each step, at least one factor \(2\) will be added to the product. Since \(n-3>\log_2n\), we know that \(2^k\) divides both \(n\) and \(b_{n-1}\), and hence also their gcd. We conclude that \(q_n\) must divide \(r\) and thus also be odd.

Puhhh… That was some piece of work! I bet I lost everyone by now. (I certainly got lost multiple times when writing this thing up.) If this easy fact already takes so much space to prove, how much longer would the full proof that \(q_n\) contains no composite have to be? I’d still be very interested to see one, it’d finally give me closure to move on from my undergraduate project… 😉

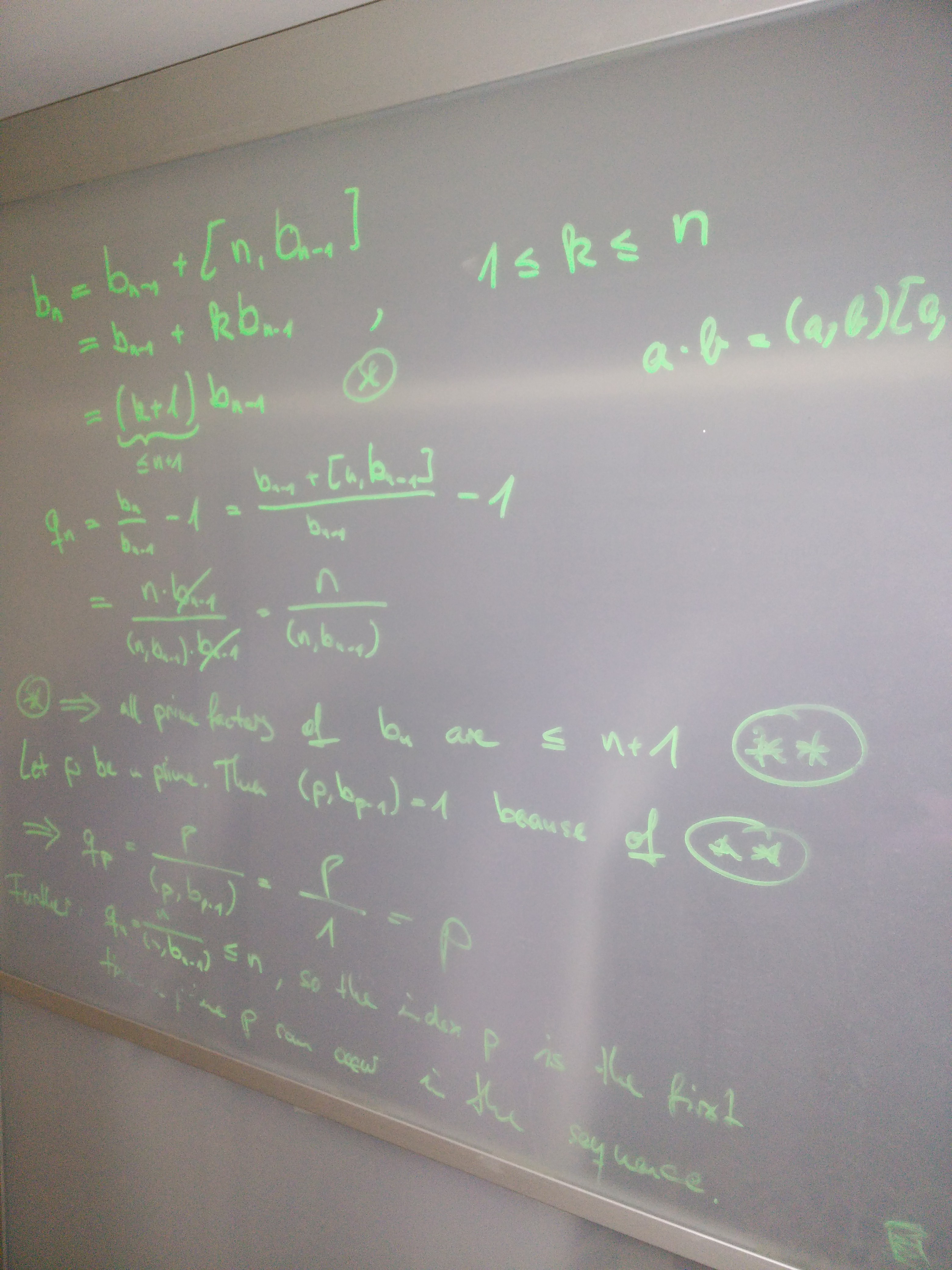

PS: This faulty proof has been on my bedroom closet for months now. Can you spot the mistake?

-

It’s common to abbreviate \(\mathrm{gcd}(a,b)=(a,b)\) in number theory, and I shall do so in the remainder of the article. Similarly, it’s convention to write \(\mathrm{lcm}(a,b)=[a,b]\). ↩︎

-

A more recent paper by Fernando Chamizo, Dulcinea Raboso, and Serafín Ruiz-Cabello sheds some more light on this question, but still only conditionally. ↩︎