Recently Matt Parker uploaded a video to his YouTube channel where he discussed numbers and the words used to represent them in different languages, more precisely the length of these words:

The basic idea is the following:

- one has 3 letters,

- two has 3 letters,

- three has 5 letters,

- four has 4 letters,

- five has 4 letters,

- six has 3 letters,

- seven has 5 letters,

- eight has 5 letters,

- nine has 4 letters,

- ten has 3 letters,

and so on… This can be seen as a function

\[ f(n) = \text{number of letters of $n$ spelled out}. \]

(Note that it says “number of letters” and not “length of word” – English and most other languages put spaces, commas, hyphens, and other decorations in between words for numbers, which we’ll ignore in everything that follows.)

As the title of the video points out, we have \(f(4)=4\). This is called a fixed point, i.e., a point that just refuses to move when you apply the function \(f\) to it. “Four” is the only word/number with this property in English. What’s more, you can repeatedly apply the word-length-function \(f\) on the result of itself, which yields a sort chain:

one → three → five → four → four → four → …

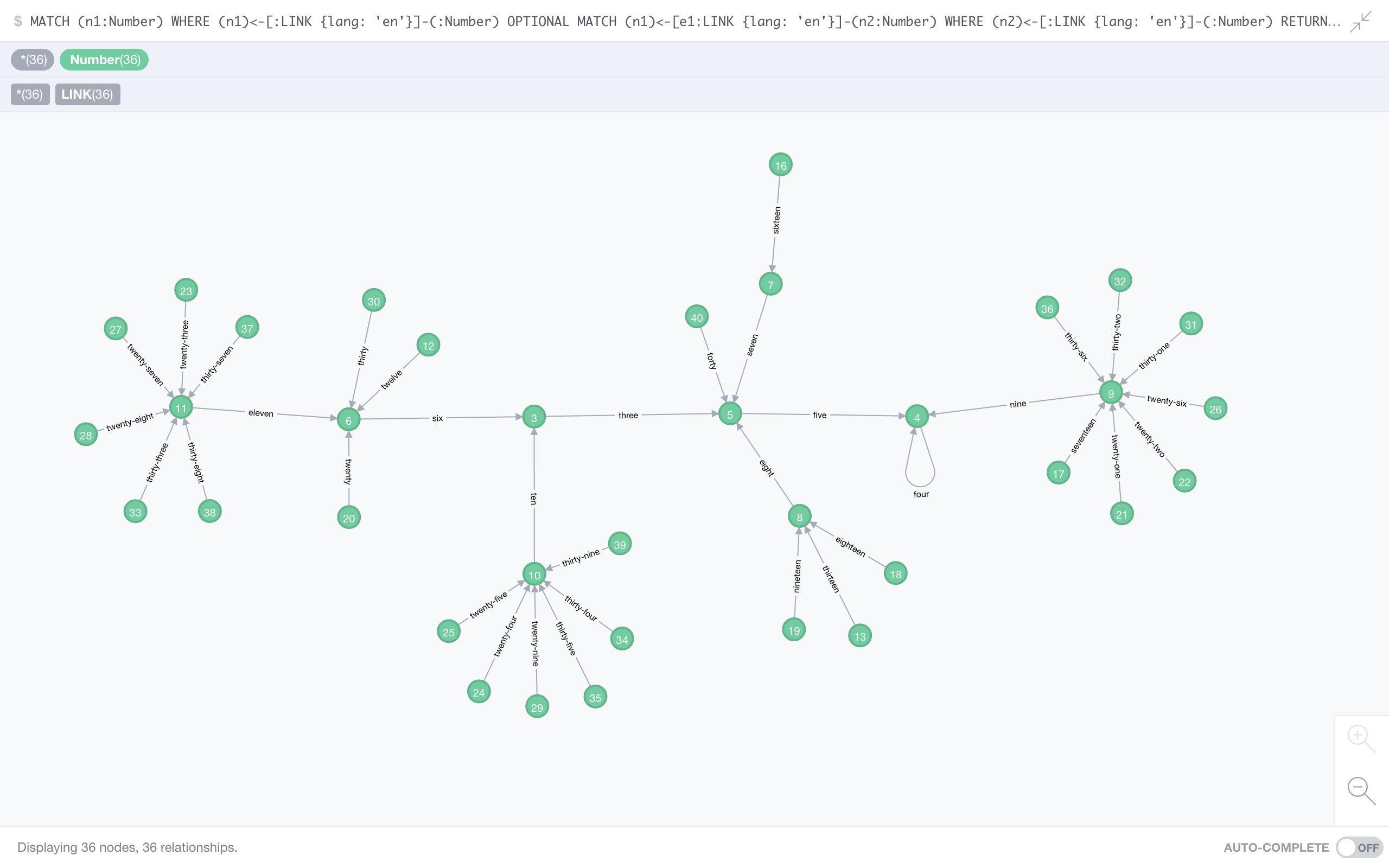

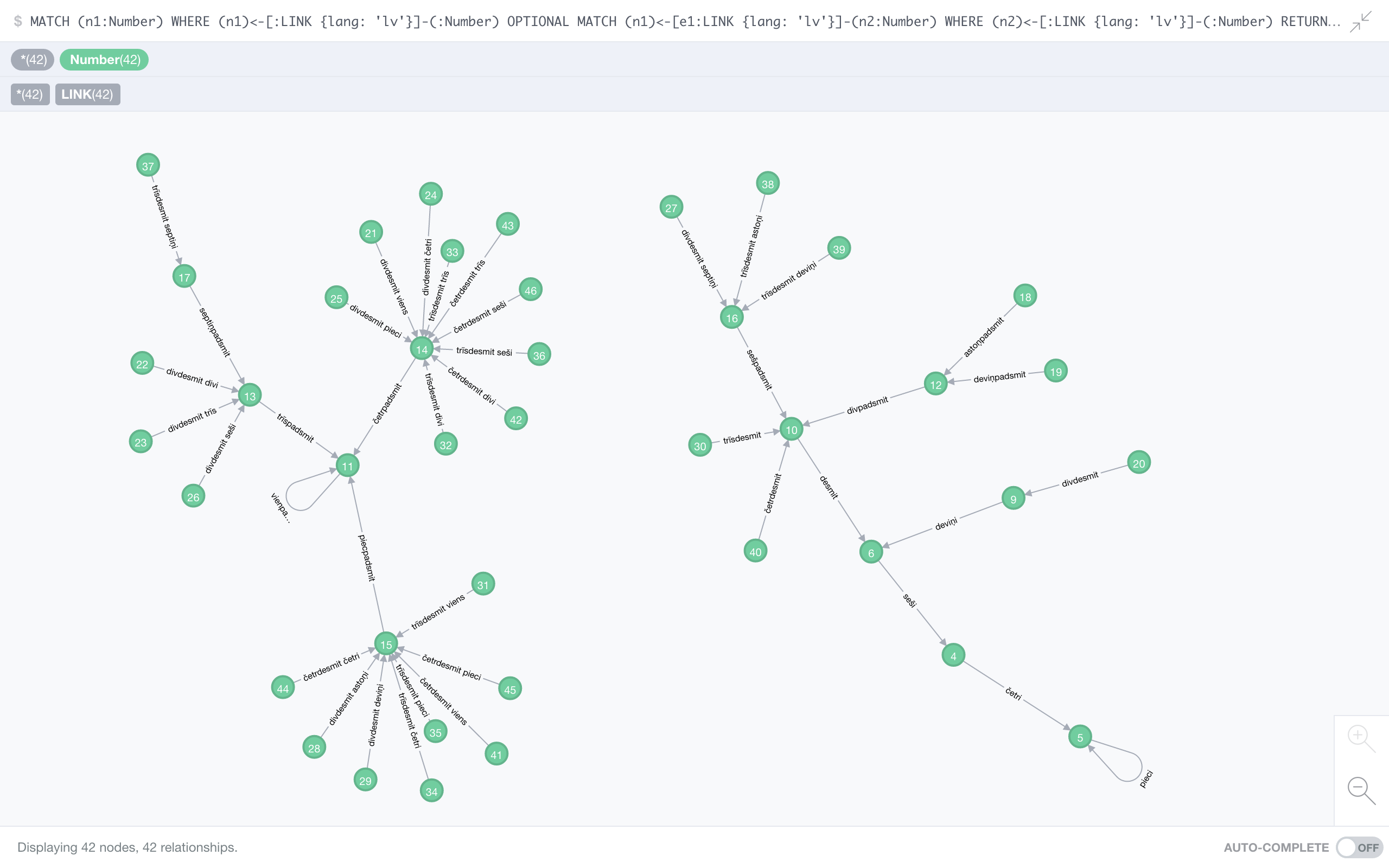

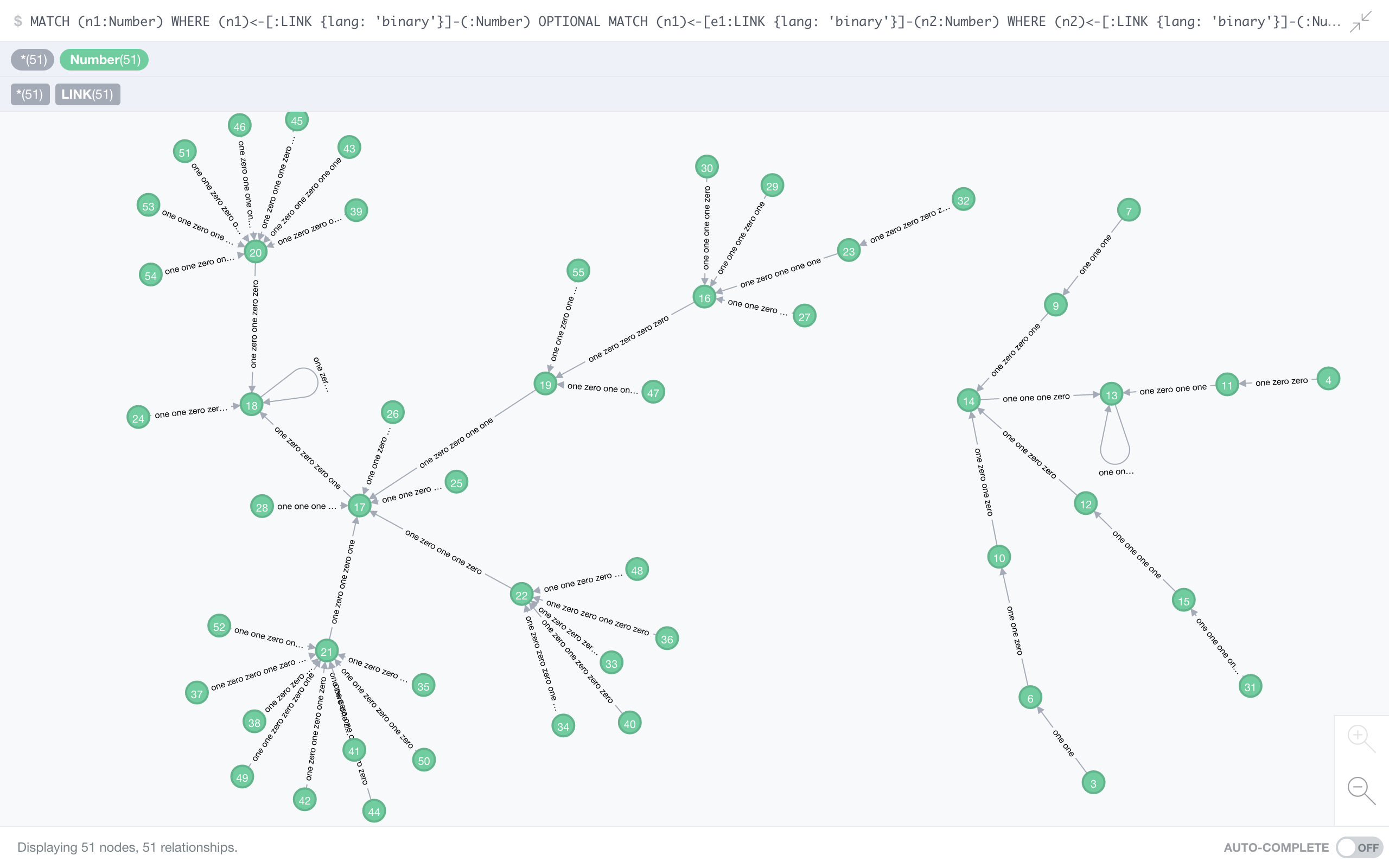

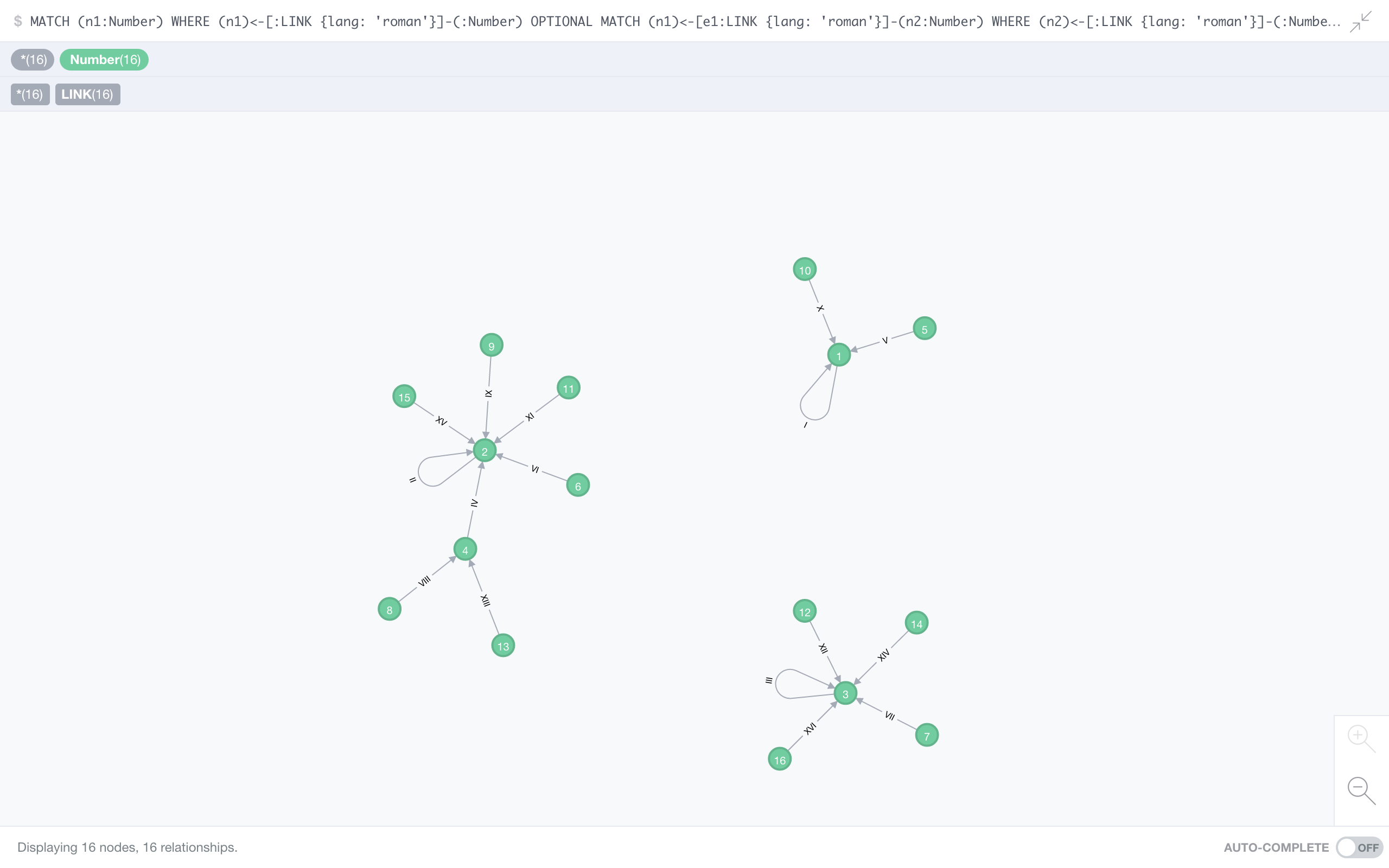

OK, we’re kinda stuck at this point. In fact, every number will eventually get stuck in this very loop when \(f\) is applied to it over and over. These chains make pretty pictures:

This graph uses every number up to 10000, but leaves out leaves (pun intended), i.e., those numbers that have no other number pointing to them. In other words: for every number you see in the graph above, there is a number (below 10001) in the English language with that length. In the original video, Matt presents a chain of length 6 (a three letter word), we can now extend that one to 7 (five letters) elements:

one hundred and twenty-four → twenty-three → eleven → six → three → five → four,

which brings us back to the infinite loop of the fixed point. This is probably a good point to discuss the inherit ambiguity in the function’s definition: natural languages are a mess. You might well have chosen to represent 124 above as “one hundred twenty-four” instead, which yields a disappointing chain of length 6. The best you can do is choose one convention and stick to it. I didn’t have much of a choice – I used existing software libraries to generate the spellings for me, so their convention is mine.

This pretty much all there is to say about English. Numerologically, it’s a pretty dull language. The graph is not particularly inspiring, no really long chains, it has only one fixed point, no other cycle, and every initial condition leads to the same number. What about other languages?

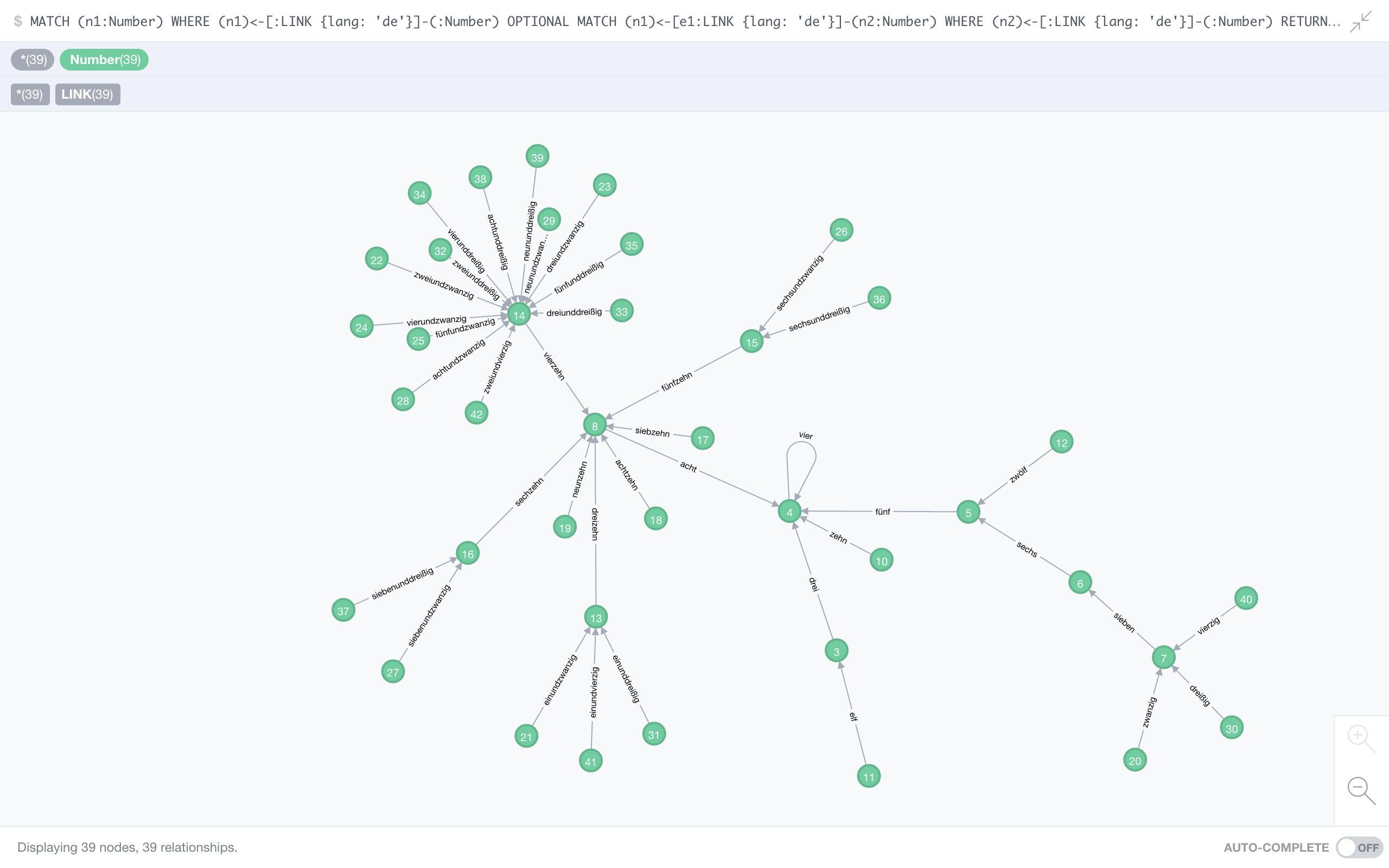

German

OK, call this nepotism, because the only reason I included German is that this is my native language. The same single fixed point as English, and no chain longer than 6. German deserves the title of dullest of all languages. Sigh…

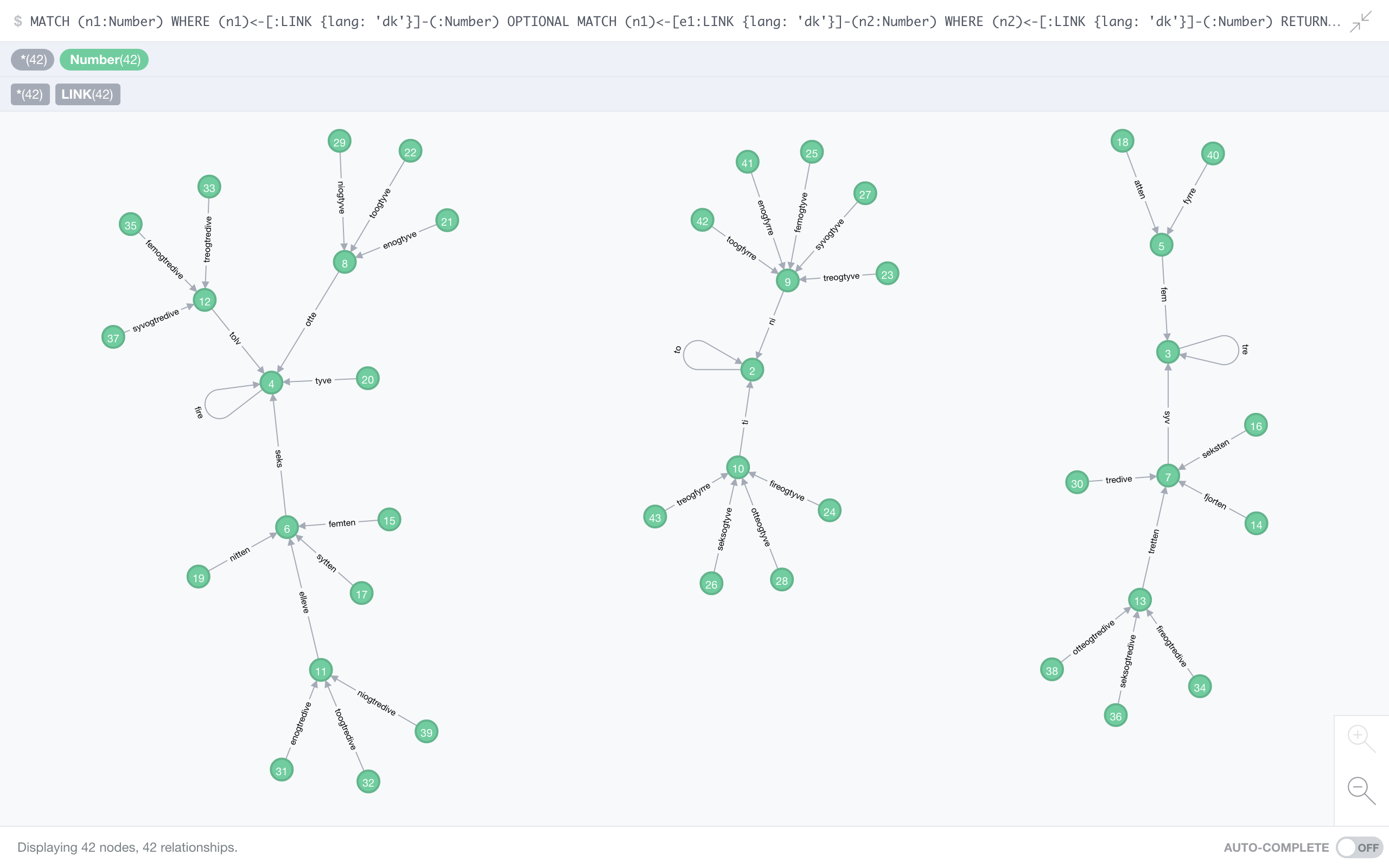

Danish

No particularly long chains, but no less than 3 fixed points. Pretty self-centred! Unlike German and English, you can categorise numbers depending on what infinite loop they will be stuck in eventually, any of the three fixed points 2, 3, or 4 (popular choices for fixed points, by the way). In graph theory, we call this the connected components of a graph. Here’s some homework for you: calculate the proportion of numbers in each connected component!

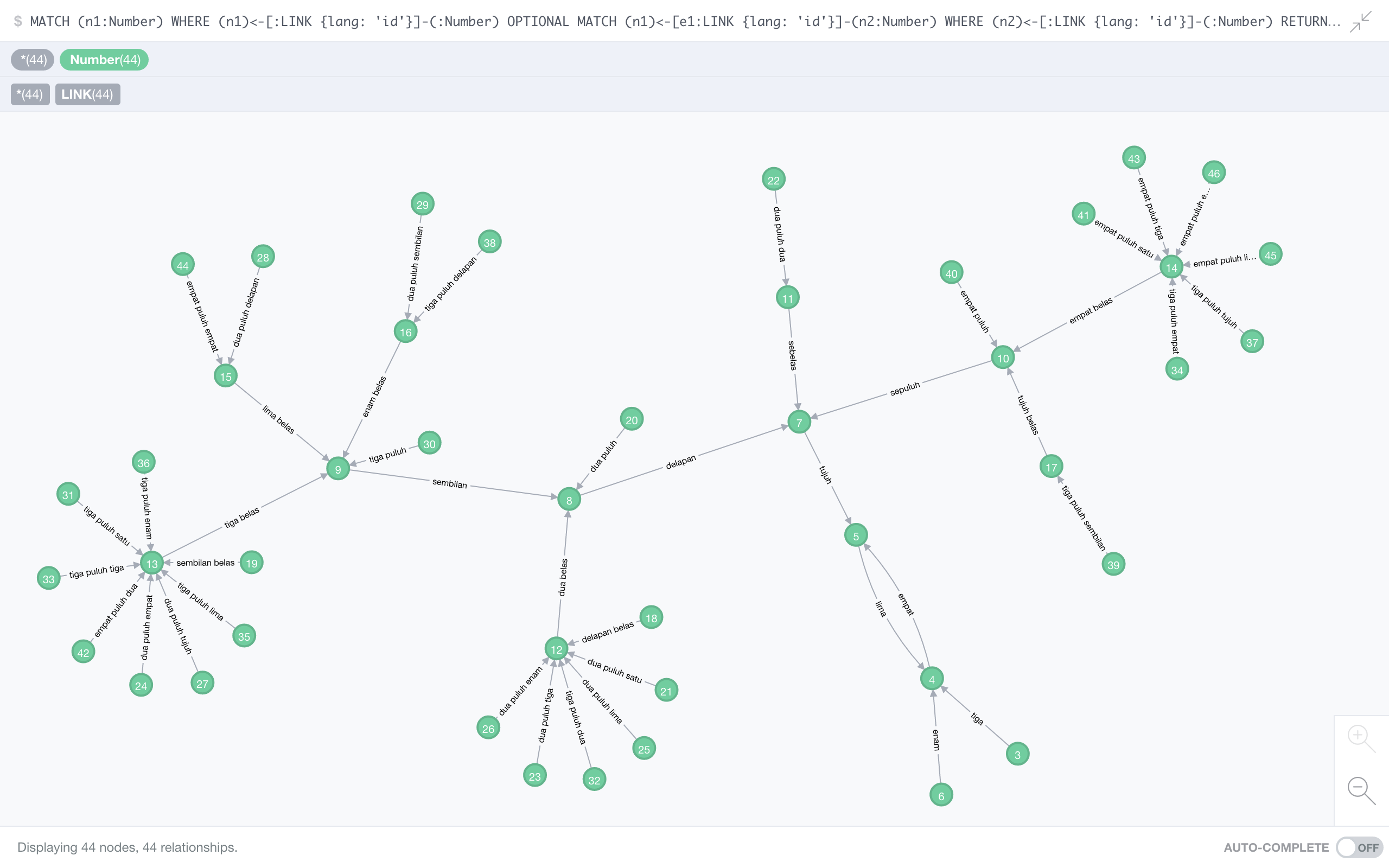

Indonesian

Indonesian is our first example of a language with a non-trivial cycle: 4 (empat) maps to 5 (lima) which maps back to 4. It also forms some pretty long chains, the longest having 8 elements:

delapan puluh delapan (88) → sembilan belas (19) → tiga belas (13) → sembilan (9) → delapan (8) → tujuh (7) → lima (5) → empat (4)

Again, there’s a bit of convention necessary how to count the chains: I opted for counting the longest chain without having duplicate members. This does favour languages with long cycles: every chain is at least as long as that cycle, plus however long it takes to reach that cycle. Well, so be it.

Esperanto

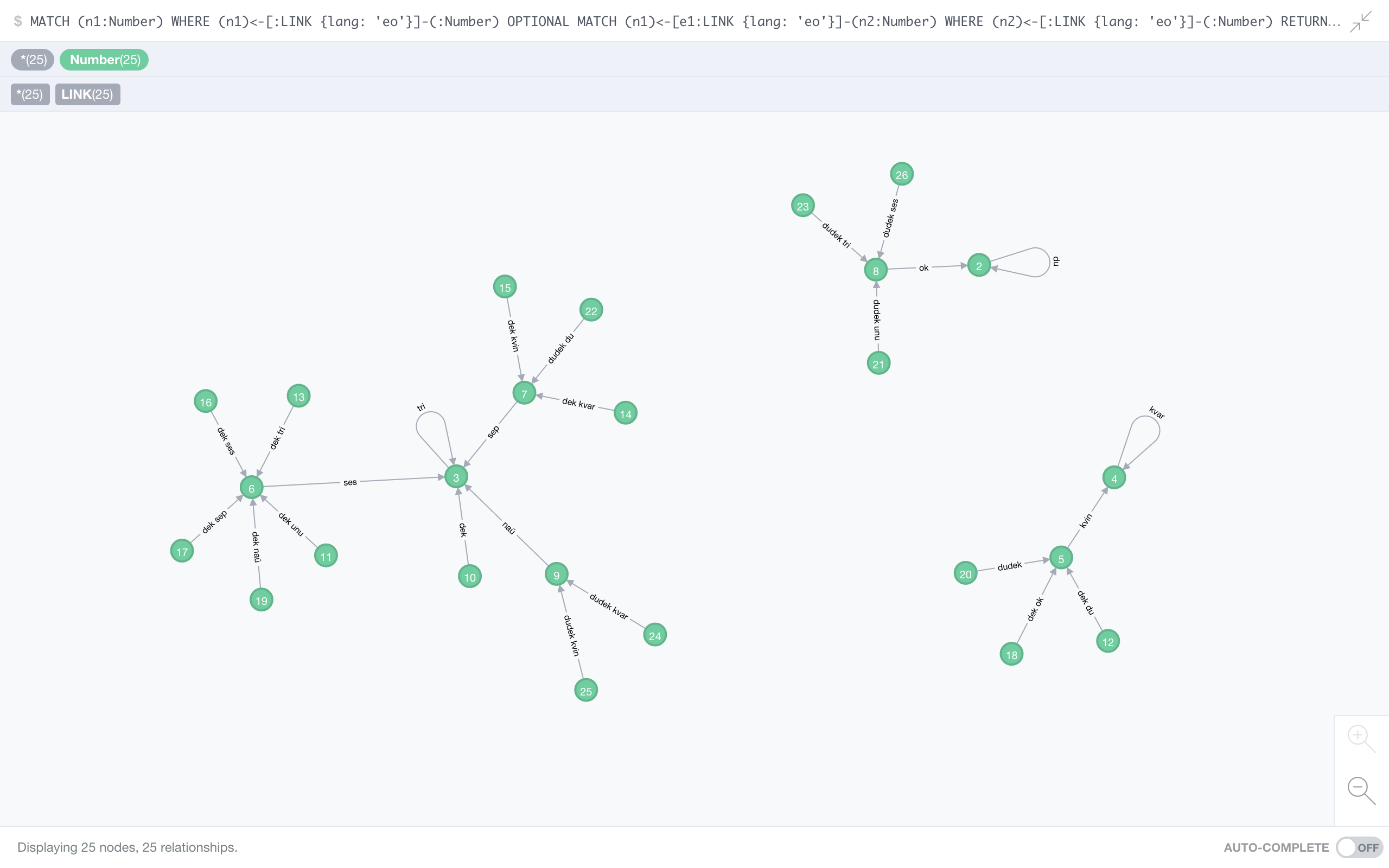

Another language that made the list mostly because of personal taste. This constructed language is as regular as it could be – generating all the number words in Esperanto takes only a dozen or so lines of code. It has the same three fixed points we’ve seen in Danish – 2, 3, and 4 – but the graph overall is really compact: the longest chain has a mere 4 members. If you think this is only possible in an artificial language, wait for our next candidate:

Norwegian

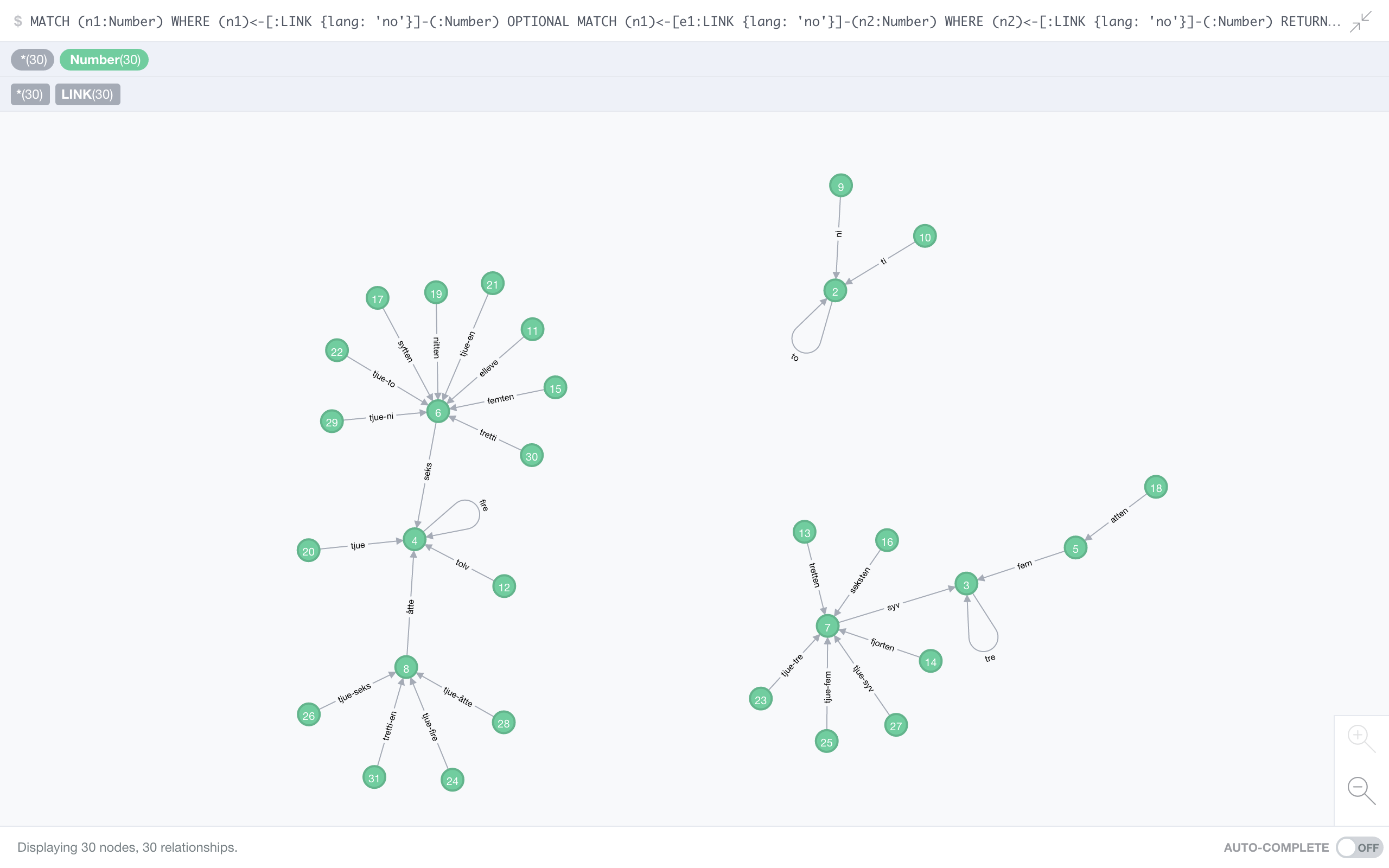

A little “bushier” than Esperanto, but the same short routes – no other natural language has shorter chains. (And again, it’s the same egoistic numbers 2, 3, and 4.)

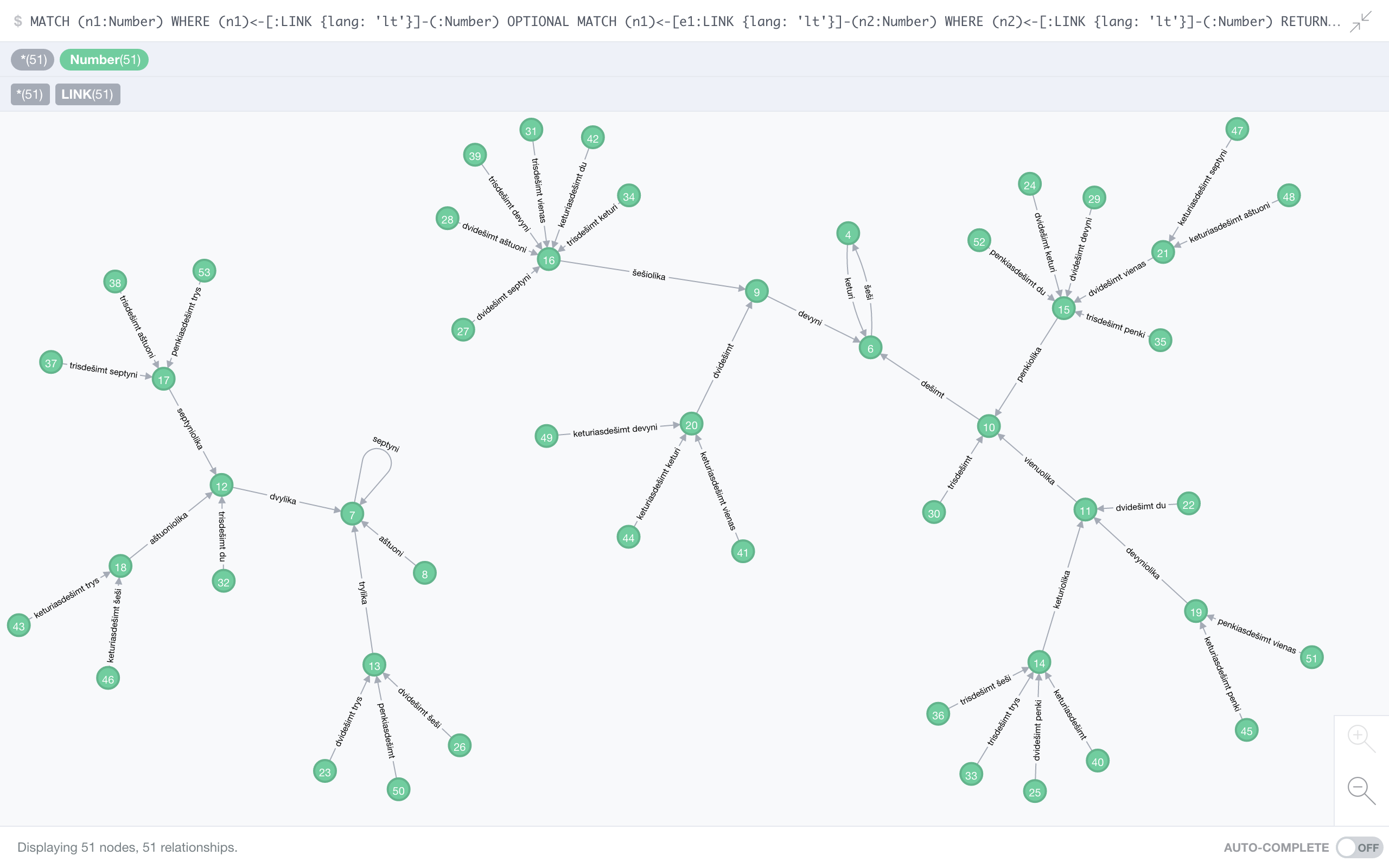

Lithuanian

So far we’ve either seen fixed points, or one longer cycle. Lithuanian has both: the fixed point 7 (septyni) and the cycle 4 (keturi) → 6 (šeši) → 4.

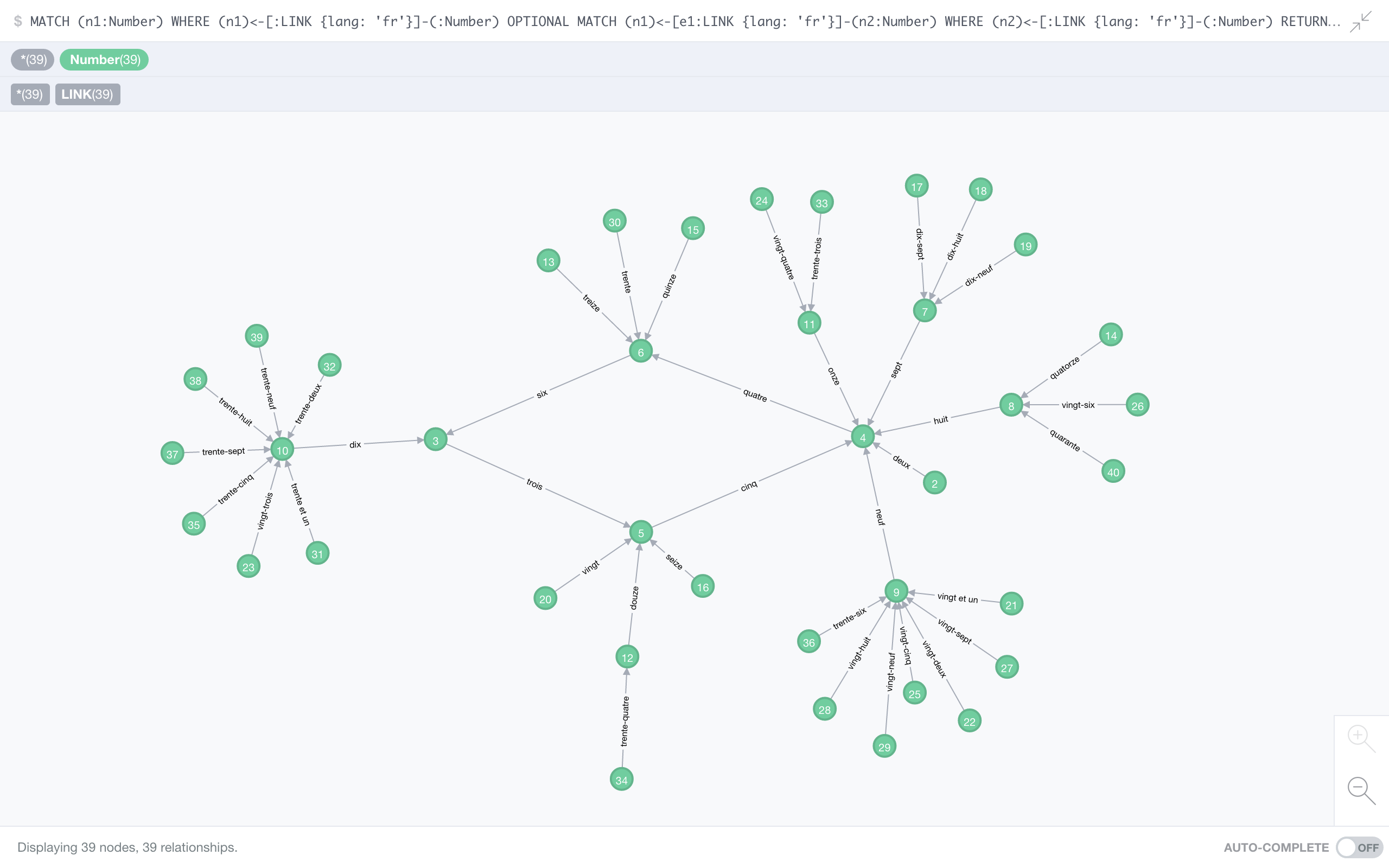

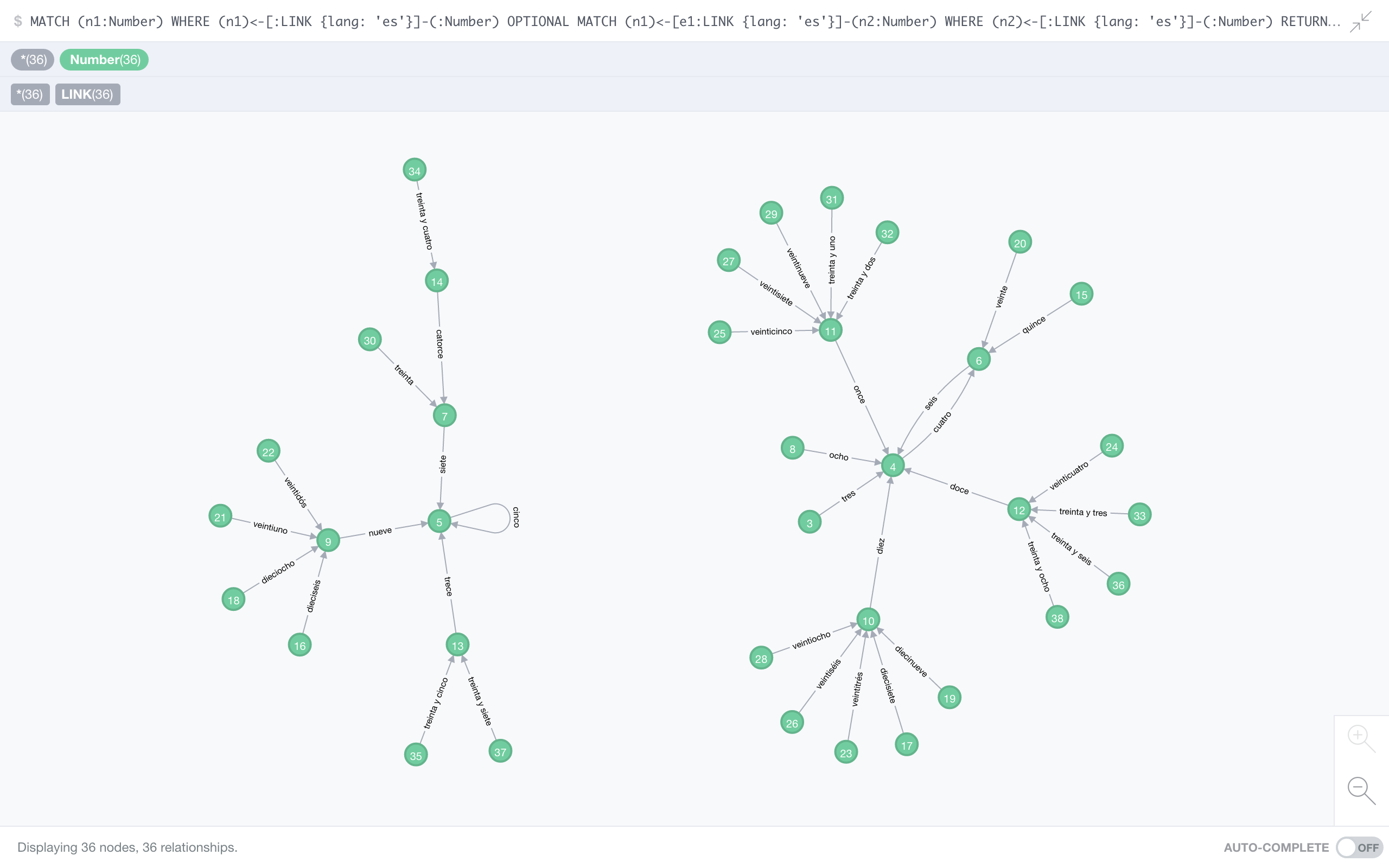

French

French boasts the longest cycle in our little survey with 4 members:

quatre (4) → six (6) → trois (3) → cinq (5)

Every number will settle in this loop, and still French has no chains longer than 7, so every number pretty quickly hits one of the four members of the omnipotent French cycle.

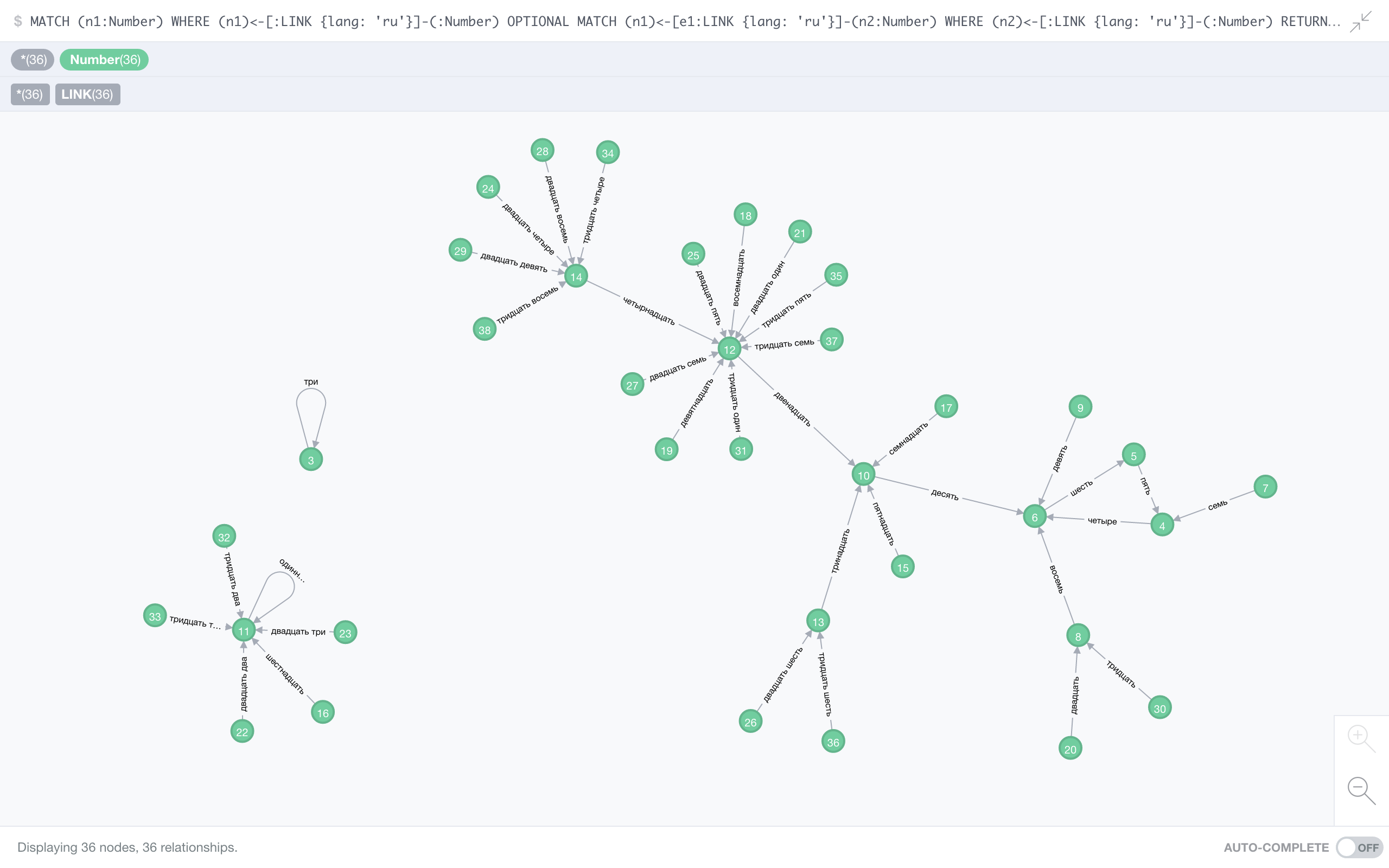

Russian

As well as being the only non-Latin script in contest, it also seems to have a pretty lonely number 3 (три). It’s not all alone though: 2 (два) and 100 (сто) point to it. Still, this is the smallest connected component we’ve seen so far. Russian also has one other fixed point (11 – одиннадцать) and a 3-cycle:

четыре (4)→ шесть (6)→ пять (5)

A lot of structure for one language!

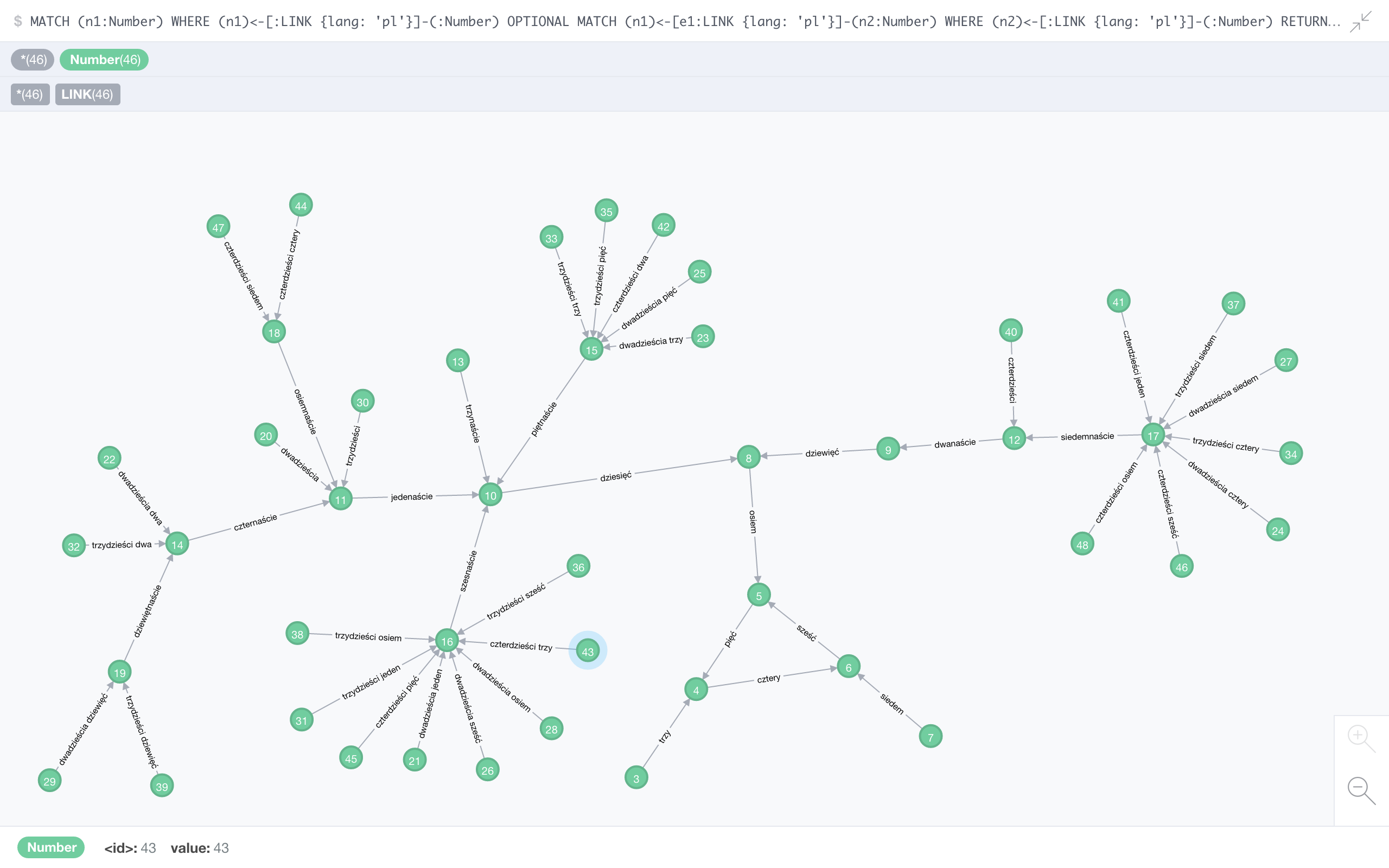

Polish

The thing you notice immediately in Polish is just how spread out it is – in fact it takes some numbers 7 steps before they reach the language’s all-consuming 3-cycle, which gives a record chain of 10 elements:

dwieście sześćdziesiąt dziewięć (269) → dwadzieścia dziewięć (29) → dziewiętnaście (19) → czternaście (14) → jedenaście (11) → dziesięć (10) → osiem (8) → pięć (5) → cztery (4) → sześć (6)

Just for the fun of it, I give you three more languages, not because they have properties we haven’t seen, but just because they’re pretty.

Spanish

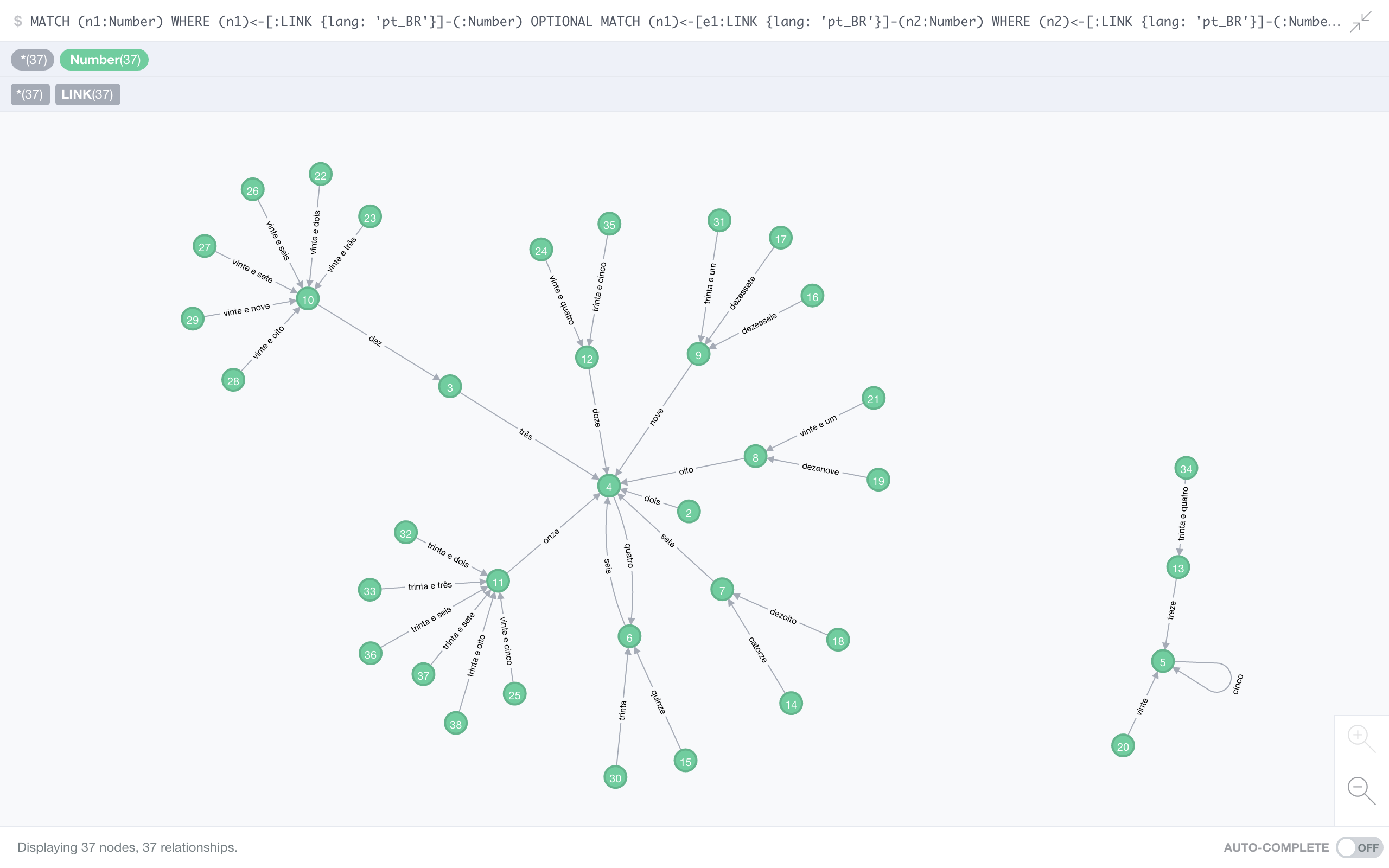

Portuguese

Latvian

But why stop at natural languages?

Binary

Matt mentions in his video binary, i.e., spelling out 10101 as one zero one zero one. The most interesting fact about this number system is the large value of its fixed point 18 – or one zero zero one zero to those who like to talk to their computers.

Roman numerals

Not strictly speaking a spelling system, yet a way of representing numbers with letters. Not surprisingly, this graph is pretty sleek – and it deserves an honourable mention since it’s the one time the number one (1) actually makes it into one of our graphs.

Matt’s \(k\) conjecture

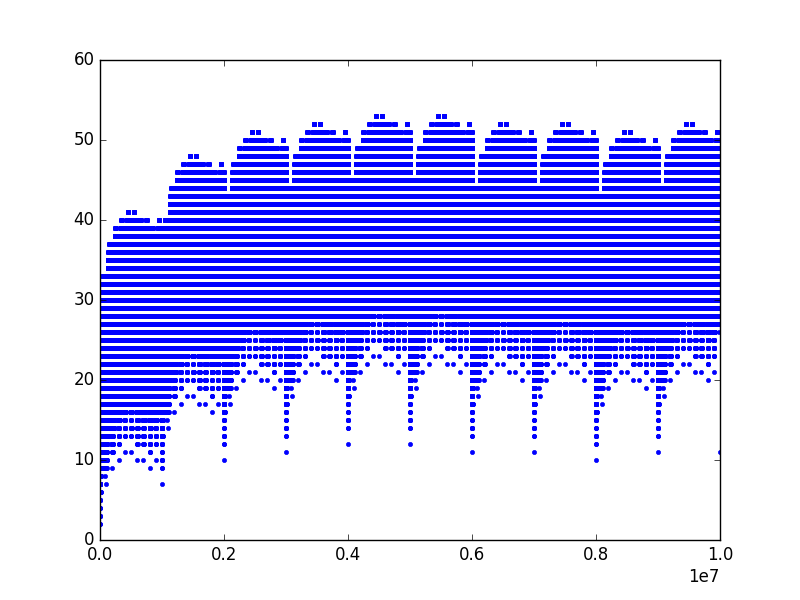

In the video, Matt conjectures that in every language there is some threshold \(k\) for which every value greater than \(k\) is mapped to a value smaller than \(k\) under that language’s function \(f\). Since most (maybe all?) languages reflect our base 10 positional number system, the information each part of the word contains when placed in front of a previous number word grows exponentially, which means that \(f\) is essentially logarithmic, so large numbers will be rapidly “passed down” to the small numbers where all the action takes place.

This plot shows the values for \(f\) in Esperanto which I chose mostly for performance reasons. It is clear just how slow the function grows.

Technical notes

If you made it this far in the article, you might appreciate a few words on how I produced all the graphics in this article. There are a few steps to it.

Spell out numbers

Despite the many exceptions, latest from numbers above 100 things get very regular and are pretty much just concatenations of what happened before, so this task screams for computer programs. Many exist, but most are dirty one-time scripts. One pretty decent Python library is num2words which is where most of the number words in this article come from. Unfortunately, the code is little messy as well, and I just wasn’t able to extend it to add Esperanto support, so I started my own project literumi (“spell” in Esperanto) which right now is mostly a thin wrapper around num2words, but that might change over time.

Since I had to rely on these software tools for the spelling of the numbers in most of the above languages I cannot guarantee their correctness – if you spot any mistakes, please do let me know!

List of numbers

There are plenty of sites on the Internet that list the first couple of numbers, maybe up to 100, in a bunch of languages. (This site really should get an honourable mention for listing 5000 languages, albeit only numbers 1 to 10.) But that’s all dictionary style and meant to be educational, not to be processed easily with a machine. This article might be the only application for it, but it bothered me that there are no readily available files where nothing but the first couple of thousand number words are listed. So – of course – I started a project for it: nombroj (“numbers” in Esperanto).

This pretty much only contains lists I could generate with literumi, but I also tried the approach of sending the English number words to Google Translate and thus receiving a list in any of their dozens of languages. But the approach has two flaws: (a) Google Translate is extremely expensive – if you use their API they charge you about USD1 for translating 1000 numbers. (b) It’s terrible – the spellings are inconsistent if not incorrect and are often interspersed with the expression in digits. And you charge for this, Google?

Graphs

All the graphs (in the mathematical sense, other people would maybe call them networks) you see above are produced with Neo4j, an excellent graph database. I wrote a small script (another project on GitHub, of course) to load the data into Neo4j, and then used their default visualisation in the browser to get the graphics – I simply made a screenshot. This is the query I used for English:

MATCH (n1:Number)

WHERE (n1)<-[:LINK {lang: "en"}]-(:Number)

OPTIONAL MATCH (n1)<-[e1:LINK {lang: "en"}]-(n2:Number)

WHERE (n2)<-[:LINK {lang: "en"}]-(:Number)

RETURN n1, e1, n2

There might be smarter ways of doing this, but I’m very much a Neo4j novice and it certainly does the trick for me.

The last plot of the function \(f(n)\) was created with matplotlib, through something like this:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from literumi import spell

mx = 10 ** 7 + 1

x = range(mx)

y = [len(spell(i, lang="eo")) for i in range(mx)]

plt.plot(x, y, linestyle="", marker=".")

plt.show()